“I am just a poor boy though my story’s seldom told. . . .”

The Boxer, Simon & Garfunkel

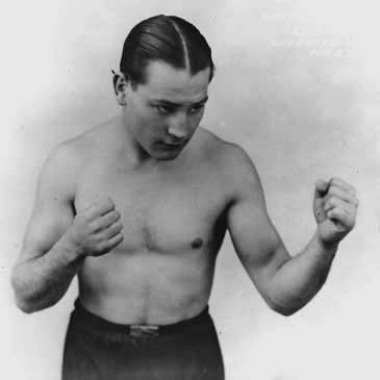

When he was “right,” one of his admirers once said, Eddie Cool, “the pride of Tacony,” was “the greatest boxer ever to come out of Philadelphia.”

But this Irish-American fighter, born in 1912, wasn’t “right” very much. He was an alcoholic who hated training and loved the ladies who, because of his matinee idol good looks, loved him back. All his life, Cool was shadowed by the death of his father who was killed in a grisly accident when Eddie was 15. He used to say “My old man died a drunk at a young age and I guess I will die the same way.”

And he did. Washed out of the ring at 27, Eddie Cool was dead at 35. The number one contender for the lightweight championship in 1936 and a counter-punching master with 95 wins and 29 losses, died from alcohol-related causes and was buried in an unmarked grave in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Cheltenham.

Today, only hardcore Philly boxing fans—and only those with a penchant for history—remember ‘the Tacony flash.” One of them is John DiSanto of Mantua, NJ, a man so passionate about boxing he has spent the last few years—and his own money—chasing down the ghosts of Philly boxing and giving them a taste of immortality on his website www.phillyboxinghistory.com. There, you can read about South Philly’s own Thomas Patrick “Tommy” Loughran, the “Phantom of Philly,” pride of St. Monica’s parish and light heavyweight champion of the world who lost the heavyweight crown to Primo Carnera by a decision in 1934. And Tommy O’Toole, “the Pride of Port Richmond,” who, after failing in his title bid in 1909, became a popular Vaudeville dancer. And Jack O’Brien, “Philadelphia Jack”,” another South Philly light heavyweight champion who changed his name from Hagen, probably because McBrien sounded more Irish.

“Different eras produced boxers from different ethnic groups,” explains DiSanto. During McBrien’s era—the late 1890s and early 20th century—many boxers were Irish. “Some people said that whoever was the most oppressed found success in boxing,” says Di Santo, who is a sliver Irish himself (there’s a Mahiggins on his mother’s side). “So there were a lot of Irish and a lot of Italian boxers of that era in Philly. You could say ethnicity was part of their marketing plan.”

But DiSanto found himself unsatisfied with providing the city’s generations of forgotten yet superlative boxers with a virtual memorial. As he researched their lives, he found that, like Cool, many were in unmarked graves. That’s when the Philly Boxing Gravestone Program was born—out of a fight fan’s determination to make sure that no boxer would ever pass entirely out of memory.

“About five years ago I was doing research on a young Philly fighter named Tyrone Everett,” explains DiSanto, as we sit in his car at Holy Sepulchre where he is finalizing plans for Eddie Cool’s gravestone, a flat marker that will be installed this fall in the Archdiocesan cemetery. Everett, who lost a world title in what’s widely considered one of the worst decisions in boxing history, died at 24—shot to death by a jealous girlfriend.

“I went out to Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, PA, to find his grave and couldn’t find a stone,” says DiSanto. “Wow, I said to myself, maybe there’s something I could do. He was a hero of mine, someone I really admired as a fighter.”

That’s when DiSanto learned that you can’t just plunk a headstone on an unmarked grave, no matter how heartfelt a gesture it is. Only a family member can do that. So DiSanto had to track down Everett’s family—and the families of Gypsy Joe Harris, Garnet “Sugar” Hart, and Eddie Cool, the first four boxers the program has memorialized.

The first three weren’t too tough. Family members still lived in the Philly area. He found the siblings of Gypsy Joe Harris in Camden. Harris, who was banned from fighting because it was discovered he was blind in one eye, died of heart failure—or, some might say, heartbreak—at 44 after a life marked by drug addiction. “They took away his license between they wanted to protect him but he probably would have had a fuller, safer life if he’d stayed in the ring,” says DiSanto. “He kicked his addiction at the end, but it was just too late.”

Sugar Hart’s brother was still alive as was Tyrone Everett’s mother. The response from the families was the same: Do it.

“They one thing I learned from this is that the family is extremely appreciative,” says DiSanto. “They like that their loved one is still remembered. I try to be an advocate for these fighters.”

Some families help raise money for the headstones. “One reason many of them are in unmarked graves is that the family couldn’t afford headstones,” DiSanto explains. “Money was short and precious and they had other needs for that money.”

In Eddie Cool’s case, there may have been something else, maybe some resentment that he’d thrown his life away, DiSanto says. “I don’t really know. He left a wife and daughter but I wasn’t able to find them.” After months of looking, he contacted a distant cousin of Cool’s who gave him permission to erect the flat memorial for Eddie and his brother, Jimmy, also a fighter who died young, who is buried next to him, in what is now just a grassy spot between Andreoli and Flaherty.

DiSanto is aware that what he’s doing may sound odd. People do understand the reason for, say, erecting a statue to Philadelphia’s greatest middleweight boxer, Joey Giardello, something DiSanto did this year with the help of the Veteran Boxers Association-Ring One, and the Harrowgate Boxing Club and hundreds of donations. He presided over the unveiling of the monument in May, near the site of the late lamented Passyunk Gym on Passyunk Avenue in South Philadelphia.

Statues honoring the great are easy to understand. Gravestones for the forgotten?

It all comes down to how you define the word “great.”

For DiSanto, there’s not a lot of difference between Eddie Cool, who died an alcoholic and whose name has faded from history, and Giardello, middleweight champion of the world from 1963 to 1965, who was invited to attend the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy and distinguished himself as a businessman and humanitarian under his real name, Carmine Tilelli. It’s all about what went on in the ring.

“I’m a boxing fan,” says DiSanto. “My Dad is a fight fan. I grew up in South Jersey and went to all the fights in Philly and got hooked. I watched fights on TV and then I read about them. I got into the history. When I hit 40 or so, I found myself becoming extremely sentimental about the Philadelphia fight scene. I thought about writing a history of it as a book, but decided to do a website . I could work on it while still doing my day job (marketing) and do a little at a time, keep adding to it. . .I can go to a fight, take pictures, write about it, and have it on the website that night.”

Since he started the Gravestone Program and launched the Giardelli statue project, DiSanto has gotten some media attention, which sometimes leaves him feeling a little uncomfortable. (When I asked him to pose for a photo pointing to Eddie Cool’s grave, he laughed. “This is how I’m usually photographed,” he quipped, “hovering over a gravestone like the Angel of Death.”)

But he’s not going to stop.

“At the end of the day I know what I’m doing doesn’t really change anything,” he says. “These guys have been dead a long time and a lot of the families are surprised that there’s anyone out there who even remembers them. But I like to think this gives me a personal bond with the fighter. In many cases I’ve become like extended family to their survivors and vice versa. . .And these fighters deserve to be remembered. Guys like Eddie Cool are worthy of remembrance. They’re an important chapter in the history of Philadelphia boxing.”

And DiSanto will make sure that it’s written. In stone.

*************************************************************

Along with his website, DiSanto every year presents the “Briscoe Awards”—named for Philly fighter Bennie Briscoe—to the “Philly Fighter of the Year” and to the participants—winner and loser—of the “Philly Fight of the Year.” This year’s Briscoe Awards will be given to IBF cruiserweight champion Steve Cunningham (his second win) and to Derek Ennis and Gabriel Rosada for their USBA junior middleweight title fight at Asylum Arena in South Philadelphia. The event will be held October 10 at the Veteran Boxers Association Club, 2733 Clearfield Street in the Port Richmond section of Philadelphia. For more information, contact John DiSanto at 609-377-6413.

If you’re also a fight fan, head down to North Wildwood on Thursday, September 24, for the annual match-up between the Harrowgate Boxing Club of Philadelphia and the Holy Family Boxing Club of Belfast, Ireland, at the Music Tent at Olde New Jersey and Spruce Avenues, a traditional kick-off to the AOH Irish Fall Festival. There are 10 bouts scheduled and the first fight starts at 7 PM. Cost: $25.